How to Embed Binary Information in Your Rust Pi Pico Firmware

Embed binary metadata in your Rust Pi Pico firmware with picotool! Learn how to store program names, versions, build dates, and more in flash, so you can easily track firmware details with a single command.

Introduction

When working with the Raspberry Pi Pico or any RP2040-based board, a interesting tools in your development toolkit could be the picotool. With picotool, you can inspect UF2, ELF, and binary images, read device information directly from a Pico in BOOTSEL mode, reboot devices, dump flash ranges, and so much more.

But here’s a really cool feature, picotool can display structured binary metadata compiled directly into the firmware. Imagine being able to see your program’s name, firmware version, build time, memory layout, or even custom application-specific information, all without writing a single line of custom parsing code.

The C/C++ Pico SDK has built-in support for this feature, but what about Rust? Today, we’ll explore exactly how to embed picotool-compatible binary information in a Rust project.

Using rp-binary-info in Embedded Rust

There is a published crate on crates.io, however, I will be using an alternative rp-binary-info module from GitHub directly.

Clone the repository or copy it into your project, typically at:

src/rp-binary-info/Then, reference it in your Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

rp-binary-info = { path = "./src/rp-binary-info" }Step 1: Update memory.x Linker Script

The picotool scans specific flash regions for binary-info headers and entries. To support this in Rust, we need to define two new linker sections:

.bi_headercontains the header and pointer information..bi_entriesholds all binary-info records.

Start by adding the following section definitions to your memory.x linker script:

SECTIONS {

/* ### Picotool 'Binary Info' Header Block

*

* Picotool only searches the second 256 bytes of Flash for this block, but

* that's where our vector table is. We squeeze in this block after the

* vector table, but before .text.

*/

.bi_header : ALIGN(4)

{

KEEP(*(.bi_header));

/* Keep this block a nice round size */

. = ALIGN(4);

} > FLASH

} INSERT BEFORE .text;

/* Move _stext, to make room for our new section */

_stext = ADDR(.bi_header) + SIZEOF(.bi_header);

SECTIONS {

/* ### Picotool 'Binary Info' Entries

*

* Picotool looks through this block (as we have pointers to it in our header) to find interesting information.

*/

.bi_entries : ALIGN(4)

{

/* We put this in the header */

__bi_entries_start = .;

/* Here are the entries */

KEEP(*(.bi_entries));

/* Keep this block a nice round size */

. = ALIGN(4);

/* We put this in the header */

__bi_entries_end = .;

} > FLASH

} INSERT AFTER .text;This ensures the sections are placed exactly where picotool expects them.

Step 2: Embed Metadata

Next, we declare the header block, mapping table, and binary-info entries. This is where the magic happens, we’re telling picotool where to find our metadata and how to interpret it.

use rp_binary_info::ID_RP_PROGRAM_DESCRIPTION;

unsafe extern "C" {

static __bi_entries_start: rp_binary_info::entry::Addr;

static __bi_entries_end: rp_binary_info::entry::Addr;

static __sdata: u32;

static __edata: u32;

static __sidata: u32;

}

/// Picotool can find this block in our ELF file and report interesting metadata.

#[unsafe(link_section = ".bi_header")]

#[used]

pub static PICOTOOL_META: rp_binary_info::Header =

unsafe { rp_binary_info::Header::new(&__bi_entries_start, &__bi_entries_end, &MAPPING_TABLE) };

/// This tells picotool how to convert RAM addresses back into Flash addresses

static MAPPING_TABLE: [rp_binary_info::MappingTableEntry; 2] = [

// This is the entry for .data

rp_binary_info::MappingTableEntry {

source_addr_start: unsafe { &__sidata },

dest_addr_start: unsafe { &__sdata },

dest_addr_end: unsafe { &__edata },

},

// This is the terminating marker

rp_binary_info::MappingTableEntry {

source_addr_start: core::ptr::null(),

dest_addr_start: core::ptr::null(),

dest_addr_end: core::ptr::null(),

},

];

#[unsafe(link_section = ".bi_entries")]

#[used]

pub static PICOTOOL_ENTRIES: [rp_binary_info::entry::Addr; 4] = [

PROGRAM_NAME.addr(),

PROGRAM_VERSION.addr(),

PROGRAM_BUILD_DATE.addr(),

PROGRAM_DESCRIPTION.addr(),

];

static PROGRAM_NAME: rp_binary_info::entry::IdAndString =

rp_binary_info::program_name(concat!("Super tool", "\0"));

static PROGRAM_VERSION: rp_binary_info::entry::IdAndString =

rp_binary_info::version(concat!(core::env!("CARGO_PKG_VERSION"), "\0"));

static PROGRAM_BUILD_DATE: rp_binary_info::entry::IdAndString =

rp_binary_info::build_date(concat!(core::env!("DATE"), "\0"));

static PROGRAM_DESCRIPTION: rp_binary_info::entry::IdAndString = rp_binary_info::custom_string(

rp_binary_info::TAG_RASPBERRY_PI,

ID_RP_PROGRAM_DESCRIPTION,

concat!("git:", core::env!("GIT_HASH"), "\0"),

);This block generates all the structures picotool needs to extract metadata from our firmware.

Step 3: Inject Info Into the Build

To make the metadata dynamic (e.g., including the Git hash or build date), you can inject environment variables during the build process. Add a build script (build.rs) to your project

use std::process::Command;

use std::{env, error::Error, fs::File, io::Write, path::PathBuf};

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let out_dir = PathBuf::from(env::var_os("OUT_DIR").unwrap());

println!("cargo:rustc-link-search={}", out_dir.display());

File::create(out_dir.join("memory.x"))?.write_all(include_bytes!("memory.x"))?;

let output = Command::new("git")

.args(&["rev-parse", "HEAD"])

.output()

.expect("Failed to execute git");

let git_hash = String::from_utf8_lossy(&output.stdout).trim().to_string();

println!("cargo:rustc-env=GIT_HASH={}", git_hash);

let formatted_date = format!("{}", chrono::offset::Utc::now().format("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S"));

println!("cargo:rustc-env=DATE={}", formatted_date);

Ok(())

}This script automatically injects the Git commit hash and build timestamp into the firmware. To add the timestamp, include a build dependency in your Cargo.toml:

[build-dependencies]

chrono = "0.4.37"Reading the Metadata with Picotool

You can use picotool to read the metadata in two ways:

Option 1: Once the firmware is compiled and flashed, set the Pico into bootloader mode (e.g., press and hold the BOOTSEL button and plug it into the computer). Then, simply run:

$ picotool info -a

Program Information

name: Super tool

version: 0.1.0

description: git:8ea00b3ab65b5ce6931fe9f414a3ab163e0aae30

binary start: 0x10000000

Fixed Pin Information

none

Build Information

build date: 2025-12-03 07:42:28

build attributes: id:12 backbone:23

Device Information

type: RP2040

revision: B2

flash size: 2048K

flash id: 0xE66178C12755622D

Metadata Blocks

noneOption 2: Provide the built .elf file as an input:

$ picotool info <path to target> -t elf

Program Information

name: Super tool

version: 0.1.0

description: git:8ea00b3ab65b5ce6931fe9f414a3ab163e0aae30

binary start: 0x10000000You can embed anything else, for example serial numbers, configuration flags, build settings, or custom data structures.

What's Next?

Now that you’ve embedded binary metadata in your firmware, you can easily track firmware details with a single command. This technique is particularly useful for firmware tracking, ensuring you always know what’s running on your devices.

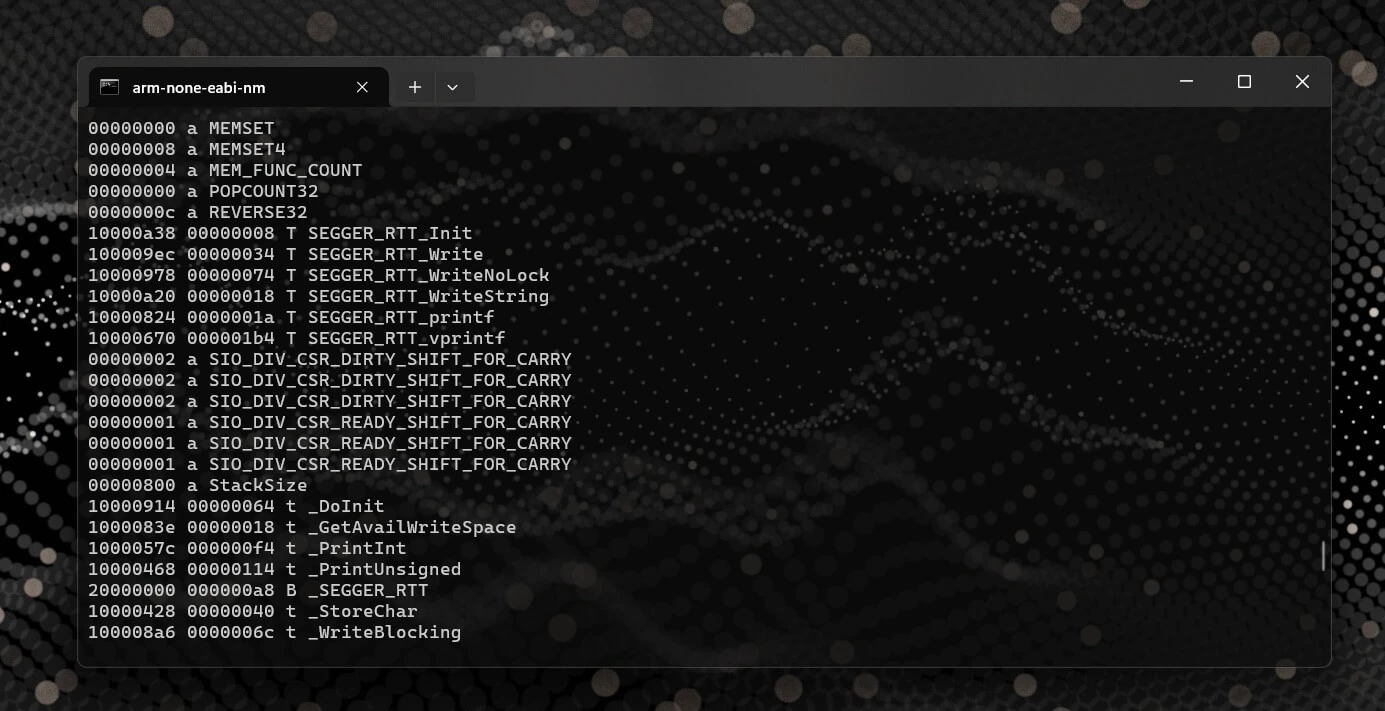

How to Find the Memory Address of a Symbol in an ELF File

A quick and useful tip for locating symbol memory addresses in ELF files using arm-none-eabi-nm combined with grep—perfect for embedded debugging scenarios like setting up SEGGER RTT or inspecting linker placements and runtime symbols.

Cortex-M0 Profiling: How to Trace Without Hardware Support

The ARM Cortex-M0 and M0+ lack hardware tracing features like SWO, ETM, and ITM, so how do you profile code on them? In this post, I explore software-based techniques to get deeper insight into performance and debugging on these resource-constrained MCUs.

How to Strip Debug Symbols from Software (and Still Keep GDB Context)

Learn how to use objcopy to strip debug symbols from an ELF executable, protecting sensitive data without losing the ability to debug your code using an external .dbg file and GDB.

Whether you're building something new, fixing stability issues, or automating what slows your team down — we can help.